By Andrew Jenck

Christopher Nolan is the only working director whose name has true brand recognition. Whereas other filmmakers of the same caliber struggle to bring their original films to screen, Nolan’s name alone can greenlight an original big-budget film fit for IMAX. Only this late into his career could he successfully pitch Oppenheimer, a film akin to his pre-Batman roots: divorced from action set pieces of his more recent films. Faced with this challenge, Nolan still delivers on the spectacle in a unique biography, framing the creation of the atomic bomb as an interpersonal journey of confronting past mistakes, filled with regret through tightly knit editing and inventive visual storytelling.

Filming a story sympathetic to the physicist responsible for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki can be polarizing considering the contested ethics, though such a goal is accomplished by fully depicting J. Robert Oppenheimer. Other biopics attempt to encompass the historic figure’s entire life, the focus here is narrower on two subjects: Oppenheimer’s sympathies to American communism and personal drive as a physicist and seeking to stop the Nazis, being Jewish. Both elements are intertwined, given the U.S. Government’s suspicions of Marxism, and employing the physicist to strengthen the government. Relatability is established by introducing the doctor as an upcoming student, prone to rash decisions and reversing them only at the last minute. Through well-written interactions with other characters, the audience learns his beliefs as a scientist and his political leanings.

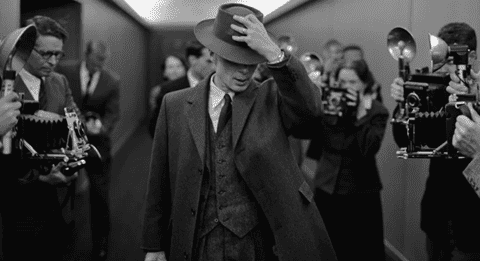

The narrative will cut to different points in time, including Oppy’s security hearings, Atomic Energy Commissioner Lewis Strauss’ testimony before Congress, and the events leading to the Los Alamos testing. Strauss’ scenes are filmed in black and white, to distinguish his view of events from J. Robert’s and give the audience a sense of his bias. Such techniques are not to disguise a simple narrative but to add layers. Often scenes from different periods will overlap, giving a glimpse into the doctor’s psyche. Laws of physics will be relayed to audiences through clever visuals that emphasis his way of thinking, giving viewers full understanding of the physicist.

Matching the tight writing is even tighter editing. With nonchronological storytelling, the editors maintain the scripts’ understandability emphasizing the character motivations and ambitions. Some can be sudden enough to jolt one out of their seat. Cinematography will create uneasiness, making the audience uncomfortable and intimate with Oppy. Cillian Murphy is extraordinary, encompassing the appropriate attitude for every point in Robert’s lifetime, emoting passion, anxiety, and dread. He earns sympathy while still encompassing a complex man prone to mistakes. Holding it all together is Ludwig Göransson’s score, woven into the script and emphasizing editing cuts and character moments. The testing of the bomb evokes Nolan’s action set pieces with a gradually building pace and heightened suspense climaxing in gorgeous spectacle.

Oppenheimer is astounding, surpassing the norms of a summer blockbuster while still being a crowd pleaser. A trip to theaters is warranted not just for its direction but for forcing the audience to feel the tension uninterrupted. It is unclear if this is Christopher Nolan’s best film, but it is the best showcase of his craft; all filmmaking elements working in such unison, tightly focused, and emotionally powerful.