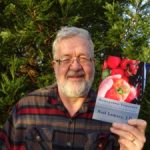

Neal Lemery – community volunteer, author and blogger neallemery.com

Books: Finding My Muse on Main Street, Homegrown Tomatoes, and Mentoring Boys to Men

Fathers’ Day is a challenging holiday, and I’m relieved it has come and gone. The event is idealized in our culture, presented as a day of barbeques, family time, and lots of smiles about idyllic childhoods and loving, kindly fathers who have inspired us, who have taught us all about love, family, and healthy parenting. It comes across as cuddly and warm, yet for many, the message is one of conflict and contradiction.

On Sunday, I had good communications with many of the men I am proud to call “son”, and good friends, guys I can talk with, heart to heart. I’m relieved that they are doing well in their emotional lives, and able to freely express their feelings with me about fathering and growing up. We’re at a stage, finally, where “I love you” is more easily spoken or written.

Yet, I have others I’ve mentored and parented who choke on saying the word “love”. I know they are struggling, challenged by how to find themselves and make sense of the confusion and chaos in their lives. Depression, addiction, broken relationships, and even jail time challenge them, as they keep searching for the tools and the paths to heal themselves and be able to move on in their lives. Guys don’t easily pick up the phone or text that they’re suicidal, high, or behind bars. There aren’t any texting emojis that say that they aren’t good enough, that they’re failures and can’t get their lives together.

I love them anyway, and try to communicate that, but often it is a one way street. Some of my letters addressed to a prison don’t get a reply, but I write anyway. I’m a gardener and planting seeds and adding water and fertilizer on what appears to be infertile ground is part of that work of faith.

Like other holidays, what we are supposed to be honoring and acknowledging conflicts with our own reality and our emotional journeys through life. None of us have lived the idyllic life, being parented with the ideal, perfect father, and living our own life free from emotional baggage left over from our childhood. We experience our own roles as men, fathers, and the complex task of helping to raise kids and navigate our own turbulent emotional waters of adulthood. The road is often bumpy.

It is a day of conflicting emotions and fake messages, including this Instagram posted on this Fathers’ Day from Bill Cosby, once television’s ideal dad, and now an imprisoned, convicted sexual predator:

“Hey, Hey, Hey…It’s America’s Dad… I know it’s late, but to all of the Dads… It’s an honor to be called a Father, so let’s make today a renewed oath to fulfilling our purpose – strengthening our families and communities.”

Emotional predators, especially those who have projected a wholesome image through the media, and hold themselves out as a role model of virtue and integrity, have no credibility coming across as the ideal dad. No, Mr. Cosby, you are not “America’s Dad” anymore, and I reject what you are trying to project upon us. Your social media posting is a mockery of what Fathers’ Day needs to be.

I’m not alone in thinking about the challenges of being both the child and the father, and dealing with sons and daughters who are conflicted about dealing with the idealization of parenting, how to emerge whole, or at least not emotionally ravaged from childhood.

I Googled “father anger” and saw there were 185 million hits. It is a rich topic for writers, and all of us who are trying to make sense of masculine anger.

“It’s not being a man that makes men prone to anger, but being socialized to be “masculine,” which studies suggest is hard to separate from a propensity for angry emotions. Societal expectations about how to be a boy are evolving, but many men are still taught that anger is one of few acceptable emotions for them to express. When toughness and independence are highly valued in men, this inevitably leads to outbursts.”

–Virginia Pelley

https://www.fatherly.com/love-money/relationships/good-dads-anger-problems/

The greeting card section at the grocery store doesn’t have Fathers’ Day cards about anger, about emotional abuse, and the challenges of having a real deep conversation with dad about growing up, and how to navigate those troubled waters.

Talking about emotions and childhood trauma are still taboo topics for many men at social gatherings, as well as one on one. I’ve also seen adult children who are called at a funeral to eulogize their parent struggle to put into words stories about their parents’ lives, trying to balance truth telling with unresolved emotions about the tough times with mom or dad. A funeral isn’t expected to be very healing for anger and rage.

However, the subtleties in the stories that have been edited to be spoken at a funeral can convey a willingness to be real, to connect with family on what has often been stuffed away in the family closet of secrets. There remains the deep need to tell the truth, and to heal.

Being open and honest about such experiences has been seeing the light of day in recent years. Popular figures have been telling their stories, and numerous books dig into the challenges of familial rage and dysfunction. The “Me Too” movement and other acts of cultural courage over the past few decades have modeled the benefits of being open and having the courage to start to heal.

In the last few years, work on addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) has been a breath of fresh air and provided opportunities for understanding and healing, much to the benefit of our society. Educators are now becoming informed and are implementing innovative approaches to helping kids.

Many of the men I’ve mentored have had the benefit of good counselors and therapists, friends, and lovers who have helped in removing the thorns of abuse, self-debasement, and emotional sabotage. For many people, the vicious cycle of generational emotional paralysis and impotent rage has been exposed to the light of understanding, and been broken, or at least interrupted. For all that work, I am heartened, and I can see society moving and changing, Bill Cosby’s recent comment notwithstanding.

I try to convey to my sons and the other men in my life that we are all entitled to our anger and our rage, that the wounds we have experienced should be acknowledged, and that healing is possible. Dealing with the mixed emotions of Fathers’ Day is part of that work. It is a reminder of how far we have come, and how far we need to go in our journeys.

6/17/2019

.png)