By Kim Rosenberg

I don’t usually write much about my personal life, but I went to a meeting the other day, and somebody I know asked about my health. They know I have a brain injury—the result of a long ago ex-husband—but because I look fine and mostly live my life, it’s not obvious that I struggle in a bunch of ways that aren’t always visible to other people.

In Why Can’t I See Straight? an article in the March 6, 2022 New York Times Magazine, Christina Hillstrom writes, “Research shows that victims of domestic violence sustain head trauma more often than football players—hinting at a hidden epidemic of brain injury in women.”

I used to not tell anyone this stuff because there’s a lot of judgment about living with someone who hurts you. There’s also judgment when you have a hidden disability that involves your brain. When people only see you on good days, they might not understand that there are bad days and what that might look like.

After I was diagnosed, I learned that women make up a significant percentage of people living with traumatic brain injuries, and many aren’t diagnosed until years after the fact, like I was. While domestic violence happens to both men and women, women make up the majority of victims and don’t always report when their partner put their head through sheet rock or used their body like a punching bag or choked them until they passed out.

It takes most people a bunch of times to leave a violent relationship for good, for all kinds of reasons—no place to go, no money to get there, and the very real fear that you might be murdered.

But part of the reason women stay is the head injury itself. If you’ve ever had a concussion, you know there’s a kind of forgetting that happens. Repeated concussions over years messes you up. In the same NYT’s article Catherine Fortier, the deputy director of TRASK, a Veteran’s Affairs research program, is quoted saying, “The TBIs that occurred in those violent relationships, that occurred in a psychologically traumatic context, showed more pronounced changes than the TBIs that occurred in a regular civilian-type accident, like a sports injury or motor-vehicle accident.”

Many women don’t go to the hospital or doctor’s office for treatment because that will make everything worse at home. In those fifteen years with my ex, I never once called the police and I never went to the doctor. I just wore a ton of concealer and missed a lot of work.

How I got out alive is a miracle to me. It was the hardest, scariest thing I’ve ever had to do, and I’m lucky to be alive. Not everyone survives the leaving. Not everyone gets a do-over.

Sometimes the pilot light goes out, and hope is lost. You’re left in the cold and the dark. I’ve been in that place, and it’s been hope that saved me—unexpected, surprising hope.

Hope doesn’t mean denying reality and pretending everything is fine when it clearly is not. That kind of hope is more like wishing.

Hope isn’t a wish; hope requires action. It’s the soul’s muscle.

I’d been working that muscle for about a year before I left with the help of a very good friend. Nobody leaves a situation like that without some kind of support, and Julie was mine. She didn’t judge me for staying, and she didn’t hate on my ex. She told me that love shouldn’t leave marks. She told me that when I was ready, I’d be able to leave. She told me that my life was a gift I forgot to open but it was waiting for me.

And then one day in July of 1991, I was sitting on the couch in another crappy rental watching Oprah after work—well, not really watching Oprah. I was waiting for my ex to come home from the bar with what was left of his paycheck. He’d be drunk and wired—a combination like rocket fuel that kept him up for hours while operating in a blackout. The payday before he’d pushed me down a flight of stairs, and I still had some bruises.

That day sitting on the couch with the sun shining through the windows, I saw my life in all its messed up reality. I knew exactly what would happen if I stayed and there was no way I could control it. It was nothing personal. I could be anybody and he’d be doing what he did. It was his addiction to substances and my addiction to him that kept us spinning. That was the day when I understood that this would be the rest of my life until I died. And he might be the person to kill me.

Or I could do something different. Hope whispered, TRY and I listened for a change.

When he came home wasted and threatened me that day, I got up off the couch and left. I walked away from everything I owned, and I didn’t go back. I left my job, my belongings, my home, everything. I took my life and started over. It didn’t get easier for years.

If someone would’ve told me then that I’d be living the life I live now, I wouldn’t have believed them. Yet, here I am.

If you or someone you love is experiencing violence, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline 1-800-799-7233 or text START to 88788

In Tillamook contact Tides of Change, 1902 2nd St., Tillamook, Tillamook, www.tidesofchangenw.org

P: 503.842.9486; Text: 503.852.9114

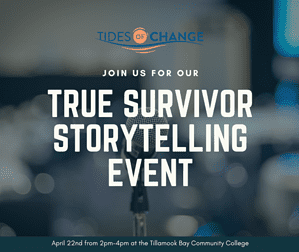

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, and Tides of Change is celebrating their 40th anniversary of providing services for hope, safety and support – to those impacted by gender based violence and shift cultural norms through advocacy, education, and community collaboration. Join Tides of Change at Tillamook Bay Community College to celebrate with “True Surivivor Stories” April 22nd from to 2 to 4 pm.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, and Tides of Change is celebrating their 40th anniversary of providing services for hope, safety and support – to those impacted by gender based violence and shift cultural norms through advocacy, education, and community collaboration. Join Tides of Change at Tillamook Bay Community College to celebrate with “True Surivivor Stories” April 22nd from to 2 to 4 pm.