By Vivi Tallman for the Tillamook County Pioneer

Two years ago this week, my 19 year old grandson died of an unintentional overdose.

Mache’s death, building on a season of other intense losses, pushed me into the swirling waters of a grief that at times overwhelmed me. I went back and forth between the security of being held by the love of my family and community and a feeling of being completely unmoored. This death was the final blow in a series of tragic family losses, and in those first months, I clung to a shred of hope that if I let myself come apart, there might be a new stronger form in which I could re-emerge.

On our north Oregon coast beaches, surfers use the rip currents as a way to get out beyond the break to catch the big waves. These are powerful narrow channels of water that rush away from the shore, and the uninitiated can get caught in them: several times a year there are drownings. Those who are familiar with these spots know not to fight the current, not to try to swim against it, but to remain calm in the force of it, and then, when the time is right, to gather one’s strength and swim sideways out of its grip.

After Mache’s death, the ripping current of grief was so strong that I couldn’t ignore it or swim against it. I had to let myself relax into it; I had no choice but to surrender and trust that when the time was right, I would be able to swim out of it. Luckily, I was graced with the guidance of others who had been there before. Eventually the raging power of grief took me out beyond the break, and offered me the opportunity to learn the art of riding the big waves of conscious grieving. I’ve been a student ever since, sometimes on top, sometimes gasping for breath, but able now to remember that I am going to be OK and that I will actually return safely, in a new found state of being fully alive. Because I’ve learned that “fully alive” must include grief.

After Mache’s death, the ripping current of grief was so strong that I couldn’t ignore it or swim against it. I had to let myself relax into it; I had no choice but to surrender and trust that when the time was right, I would be able to swim out of it. Luckily, I was graced with the guidance of others who had been there before. Eventually the raging power of grief took me out beyond the break, and offered me the opportunity to learn the art of riding the big waves of conscious grieving. I’ve been a student ever since, sometimes on top, sometimes gasping for breath, but able now to remember that I am going to be OK and that I will actually return safely, in a new found state of being fully alive. Because I’ve learned that “fully alive” must include grief.

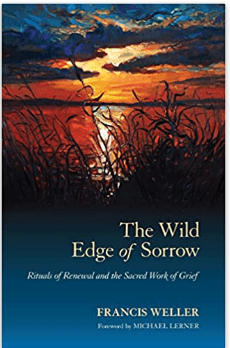

A central influence in my grief initiation has been The Wild Edge of Sorrow, by Francis Weller. I’m rereading this book today, remembering what a life buoy it was, and still is. Weller is a psychotherapist who specializes in grief counseling, and he shares his personal and professional insights as well as the poetry and prose of writers through the ages whose words lead us into the inevitable bittersweetness of life, at once painful and beautiful. Weller’s book helped me to develop a practice of grief that reminds me on a daily basis that while yes, my grief is singular, it is also profoundly universal. All across the world, families know the pain of loosing their children, and I am one of those now. I have such compassion for them as well as for myself and my family, connected without reserve to the human experience of grief and loss. And, widening the lens, I tune into myself as a drop of water in an interconnected ocean of plants, animals, stones and molecules, part of the breath of the world, and I feel the relief of letting myself know this truth. From this vantage point, and with the guidance of Weller, I can begin to tolerate seeing the full truth of what we humans are doing to our planet, and yet at the same time how the earth also continues to offer us the strength of her awe inspiring beauty. Weller’s work has opened me to a whole variety of griefs of which I had not been conscious.

A central influence in my grief initiation has been The Wild Edge of Sorrow, by Francis Weller. I’m rereading this book today, remembering what a life buoy it was, and still is. Weller is a psychotherapist who specializes in grief counseling, and he shares his personal and professional insights as well as the poetry and prose of writers through the ages whose words lead us into the inevitable bittersweetness of life, at once painful and beautiful. Weller’s book helped me to develop a practice of grief that reminds me on a daily basis that while yes, my grief is singular, it is also profoundly universal. All across the world, families know the pain of loosing their children, and I am one of those now. I have such compassion for them as well as for myself and my family, connected without reserve to the human experience of grief and loss. And, widening the lens, I tune into myself as a drop of water in an interconnected ocean of plants, animals, stones and molecules, part of the breath of the world, and I feel the relief of letting myself know this truth. From this vantage point, and with the guidance of Weller, I can begin to tolerate seeing the full truth of what we humans are doing to our planet, and yet at the same time how the earth also continues to offer us the strength of her awe inspiring beauty. Weller’s work has opened me to a whole variety of griefs of which I had not been conscious.

Today I am visiting the spot we have made for Mache’s ashes, where we honor as well his cousin and my grandchild Geneva who also died in 2020. We are lucky to have a family place where we can create an altar to these young people who died too young, a place we can visit to remember and sit with them. Now, given what Weller calls my “apprenticeship with sorrow,” I am able to come to this site and also be present with ancestral griefs that previously I wouldn’t have recognized. I can have a wider view that encompasses the native people who once traveled across this rainforest land, as well as the loggers that worked here in the early 1940’s. I can sit with the after effects of the divorce of family members who owned this land in the 60’s, and I can hold in love all the human players in this history.

The key for me is to stay present to my grief, because I have found that when I am able to do that, I am also able to experience the infinite and vast space of peace within which these sorrows sit. In this process there are many guides, and ultimately each of us must find our own, but I can say that along with The Wild Edge of Sorrow, I continue to be helped by reading buddhist teacher Pema Chodron, by attending grief rituals based on the work of Sobonfu Some and hosted by CascadiaQuest in Eugene, by the wisdom of the twelve steps, by the persistent love of my friends, family and community, and by time spent wandering in our local woods and waterways.

As Weller writes in the preface to his book, “Grief work offers us a trail leading back to the vitality that is our birthright. When we fully honor our many losses, our lives become more fully able to embody the wild joy that aches to leap from our hearts into the shimmering world.”

Grief comes in all shapes and sizes, reflecting losses from the past and the present. If you are interested in continuing this conversation, and forming a group to read and reflect on The Wild Edge of Sorrow, please contact me at vivi@nehalemtel.net.

.png)