EDITOR’S NOTE: I’ve had the wonderful opportunity to work with Neal Lemery, and I’ve shared his “musings” quite often here on the Pioneer. He has a way with words — often articulating exactly how I’m feeling about a particular issue or situation. When we met earlier this week, we discussed how much the Supreme Court confirmation was impacting so many people, and I commented, “It must be really difficult for you …” He sighed and said, “I should write something about it.”

Here is a wonderful, thoughtful view from a lawyer and a judge.

Thanks, Neal.

by Neal Lemery

I’ve listened to a lot of stories, especially stories of pain, trauma, embarrassment, and horror; people telling me the deeply personal, intimate, and heart-wrenching tales of their lives, unburdening themselves, or just sharing so that I could understand their lives better.

When I became a lawyer, the judge swearing in all the new lawyers reminded us that we new attorneys were also counselors at law, that we were healers of social ills and menders of the social fabric.

A friend of mine, a priest, kept reminding me that I, too, wore a collar and people came to me to make confession, and receive absolution and a sense of peace and healing.

“Forgiveness,” he would say, “is what we both offer the world.”

My professional life has involved a great deal of truth seeking and pursuing justice. That work necessitates actively listening, involving more than willing ears and a reasoning, analytical mind. There is also heavy lifting for the soul, and one’s gut and heart.

One’s life experiences and one’s very essences of humanity are also in play.

And just when I think I am old enough, experienced enough, to have mastered my listening and my truth detection, life throws me a new curve ball, renewing my challenge to be the consummate and empathetic discerner of reality – the knower of Truth.

Everyone’s story, everyone’s reality and truth, is different. Shaped by their experiences, their circumstances, their own truth is unique to them. And whether I judge their story as subjective, relative truth, or objective, absolute truth, it is still their story and their reality.

And I filter their story through my own lenses, my own experiences and reality, both good and bad, often flawed and more self-serving that I am inclined to confess. I’m a work in progress myself.

The wearing of the judge’s robe is too often only a symbol of the values of impartiality, truth seeking, and justice. Judging is, after all, an art and not a science. Bias, prejudice, and intolerance aren’t left at the courtroom door. Judges, after all, should see our own flaws.

Like the rest of America, I’ve been awash in the politics and story telling of seating our new justice of the Supreme Court. That process should call upon our highest and most sacred ideals as citizens. Lately, we’ve fallen far from that standard.

My senses have been flooded with profoundly emotional storytelling and speech making.

My own experiences, recollections and often buried memories of my own alcohol-infused youth have risen to the surface, adding intense anguish, empathy, and revulsion to what I am seeing on the TV news and reading in the media. The needed discussions and accountability work haven’t been at center stage.

The stories and the memories are disquieting, uncomfortable. But they need to be told. We as a society need to take on the traumas of sexual violence and over-indulgence of alcohol. The issues and questions are vital social concerns that affect all our lives and the well-being of our society.

Like other personal and societal secrets and tragedies, these stories need to be shared and understood in the bright sunshine of thoughtful and compassionate conversations and meaningful discussions.

In their telling, and in the presence of empathetic listening, there can finally be a release and an understanding, even acceptance, of history that can empower us and begin to heal us, so we are able to move ahead. Their story can no longer be locked away and buried.

Hopefully, in the telling, and the sharing, the darkness fades and fresh bright light can offer some cleansing. The festering wounds can drain and begin to heal. We all deserve to heal.

We can offer each other the gift of catharsis, the purging of infection and disease, the enlightenment of confession and forgiveness. The power of truth telling is an act of personal liberation, of empowerment.

Ending the silence is an act of disarming the abuser, a cutting of chains that have kept so much of our souls in captivity. It is an art of taking back our power and our human spirit.

In that work, that telling and sharing, there is liberation, an act of self-affirmation. When that work is being done, one gains a new sense of self-esteem and power over one’s life. It is a gift to yourself that does change your life. It is an act of self-kindness and self-respect.

It seems easy for us to recognize the truth in another person’s story. We are often quick to judge. In recent years, that rush to judgement often is skewed by labeling, blaming, categorizing, and simply being mean and vindictive. The polarizing, divisive lens of national politics artificially is shined on the story, encouraging us to quickly, and with little fact gathering or reason, qualify a tale as true or false. We have polarized compassion and patriotism.

Such a twenty second sound bite approach ill suits the truth seeking that we would want others to apply as they listen to our own stories. Don’t we want the listener of our own tale to be compassionate, wise, and a healer of our fellow human beings?

I’ve learned, as a lawyer and a judge, to be not so quick to judge, and to not rapidly label or categorize. Reality is complicated, and we can be inclined to edit and change our own stories. Each of our own viewpoints, our perspectives, are unique. Guilt, shame, self-protection, and ego all come into play so we can prepare to step out onto the stage and share our story, even if it will be told only to a trusted friend over a cup of coffee.

On the national political stage, where the stakes are higher, I think we often edit and rearrange and alter the story to attract a more receptive audience. We play the game of politics. Yet, the naked, raw truth can be brilliant and illuminated, shining through all the political and moral clutter. Bare truth can be frightening to the politicians, because of its purity and reality. Real, pure truth is not playing the game according to the rules.

For some time, I mentored a young man, holding him close as a son. He had a troubled, angry life, dealing with many problems and issues. He felt worthless and unloved. His soul pain bled all over his life.

One day, he and I took that pain on and explored his wound, looking for his truth. Years of shame, guilt and self-loathing stood in the way, but he persisted with profound courage and intestinal fortitude. In all that muck, he found his truth and spoke it out loud, so we could better hear it. It was awful, horrific, heart-wrenching. But, his truth was his and he spoke it.

And, I listened and I believed him. Believing someone’s story is so amazingly powerful and liberating. Much of his pain and anguish began to be released. And the healing began for him.

I was reminded that day of the power of unconditional love. And not the unconditional love of a listener, but that very special unconditional love he found that day for himself, that he really could speak and share his truth.

We have all hear true stories. Honest, open heart surgery kinds of experiences, unadorned by excuse making, window dressing, and self-glorification. We know it is true because our very being senses that. Our soul knows it is truth.

“You will know the Truth, and it shall set you free.” (John, 8:32)

I hope that we, as individuals, and as a country, can honor our respective truths, and in that recognition, find our common humanity.

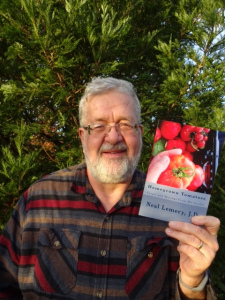

For more of Neal’s writing, check out his books: Finding My Muse on Main Street, Homegrown Tomatoes, and Mentoring Boys to Men, or his blog at www.neallemery.com.