by Neal Lemery

Many of the mysteries of the Brooten baths and sanitarium in Pacific City were revealed to a curious crowd in Pacific City June 14.

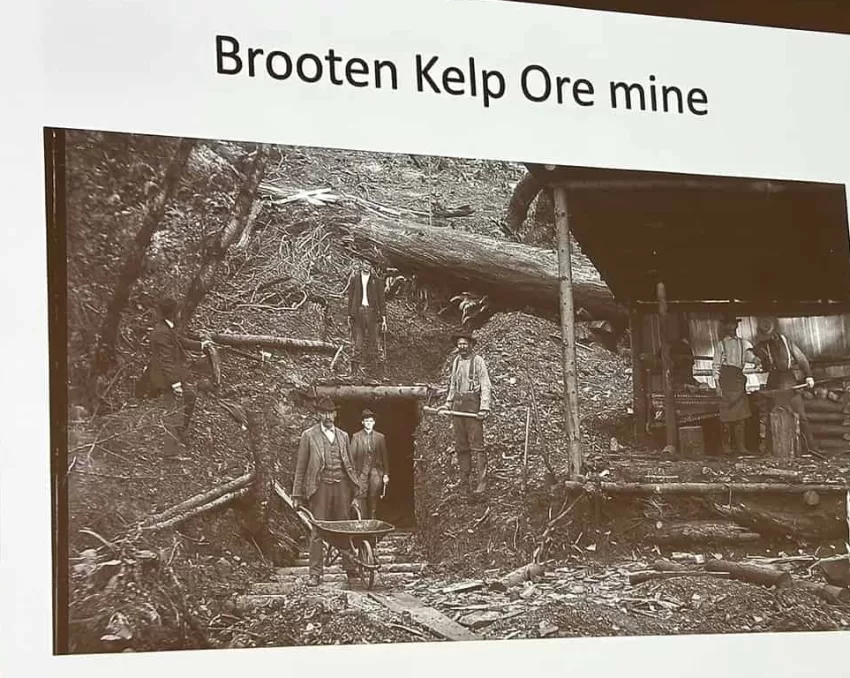

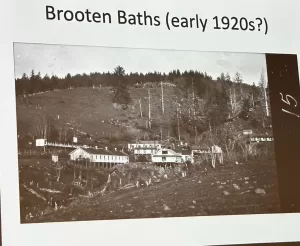

The kelp ore baths were a mainstay of the south county economy from the early 1900s to the mid 1940s, using a local sulphureous clay that was mined on the property. The clay was used as an additive to spring water and visitors soaked in over 50 bathtubs on the property adjoining the north shore of Nestucca Bay. Patrons “seeking the waters” stayed in cabins, dormitories, and later, a 13 room hotel featuring full service dining.

The clay, whose ties to kelp seaweed has yet to be established, was thought to have medicinal qualities. The clay is believed to have marine origins and is between 58 and 165 million years old.

Patrons reported favorable results from the treatment and therapy for a wide range of ailments, including diabetes, asthma, tuberculosis, cancer, bladder disorders, infections and swollen legs. The medicinal value of the mineralized clay has not been thoroughly studied by scientists.

The clay was discovered by Hans Brooten, who homesteaded the property and then developed the sanitorium, beginning in 1904. A Norwegian immigrant who had farmed and ranched in Minnesota and North Dakota, Mr. Brooten had a recurring dream of mining ore and helping people who were suffering a variety of ailments. Aspects of that dream called him to the Oregon coast. He felt called to respond to that dream, and to live a life of helping others regain their health.

The clay was discovered by Hans Brooten, who homesteaded the property and then developed the sanitorium, beginning in 1904. A Norwegian immigrant who had farmed and ranched in Minnesota and North Dakota, Mr. Brooten had a recurring dream of mining ore and helping people who were suffering a variety of ailments. Aspects of that dream called him to the Oregon coast. He felt called to respond to that dream, and to live a life of helping others regain their health.

A stay at the sanitorium included well balanced diets featuring produce from his extensive gardens, luxurious beds, exercise, dancing, frequent sips of kelp ore infused spring water, and kelp ore soaks in the numerous tubs on the property.

A stay at the sanitorium included well balanced diets featuring produce from his extensive gardens, luxurious beds, exercise, dancing, frequent sips of kelp ore infused spring water, and kelp ore soaks in the numerous tubs on the property.

The sanitorium proved a popular spa destination, attracting over 8,500 visitors from around the country, Canada, and the world, with resident naturopaths and others interested in the healing arts. The facility was a boon to the local economy, and was the primary impetus for the fledging village of Pacific City. Early patrons would arrive by horse-drawn stagecoach in Hebo and then travel over log-paved (“corduroy”) roads by horseback to the sanitarium.

Speaker and historian Cameron LaFollette has extensively researched the baths and the rise and decline of the popular sanitarium, presenting numerous photos and anecdotes. Many members of the Brooten family were present, with some of them now marketing dried powder from the famous gray-blue clay on the property. The family home has been lovingly rehabilitated, but few of the other structures remain. Some buildings were moved into Pacific City and are still used today.

The sanitorium’s popularity stimulated the appearance of other health spa facilities in south county, including the Kiawanda Sanitarium in Woods. Brooten Road, a main thoroughfare in the area, is named for Mr. Brooten.

In the 1930s, the federal government began to challenge the health claims of the Brooten baths, as well as the rest of the nation’s popular patent medicine industry. That inquiry led to a government report concluding that using the clay as a medicine was “useless” for medical purposes. The Great Depression and the advent of World War II also contributed to the decline of the baths.

The evening’s host, the Kiawanda Community Center, made this statement after the evening event: “The Brooten family was present and offered even more insight to how their family name is iconic in our area in relation to the road where the infamous Kelp ore, spa and sanitarium once stood. The “Brooten Baths” were a major economic enterprise in the sparsely settled region of Tillamook County back in early 1900’s. The full house crowd stayed for the entire presentation and were heard walking away with comments like: ‘Amazing use of my evening’, ‘What a great presentation and it was wonderful to see so many of my neighbors tonight’, and ‘I learned so much more than I had already researched on this but now I’m even more curious about other local history’.”