EDITOR’S NOTE: As we celebrate the meaning of Thanksgiving, and Native American Heritage and history, Don Backman explores a hike that has many meaningful messages about the plight of our local tribes. Many continue to fight for recognition, reclaiming ancient lands and rebuilding cultures. The more we know about this history, the more we learn about our natural environments, and living as one with the earth.

By Don Backman

We could feel the crashing waves through the ground. The ocean, kicking up some from a recent weather system, roared just yards away. Mike pointed at a bench situated close to the waves. “That looks like a good place to get wet in a storm,” he commented.

What are we doing on the beach? Isn’t this article about hiking? It was early on October 14th, 2021, we were in Yachats, Oregon, and we were gearing up to hike Amanda’s Trail. Only a short section of grass and rocks separates the parking area at Yachats Ocean Road State Natural Site trailhead from the waves.

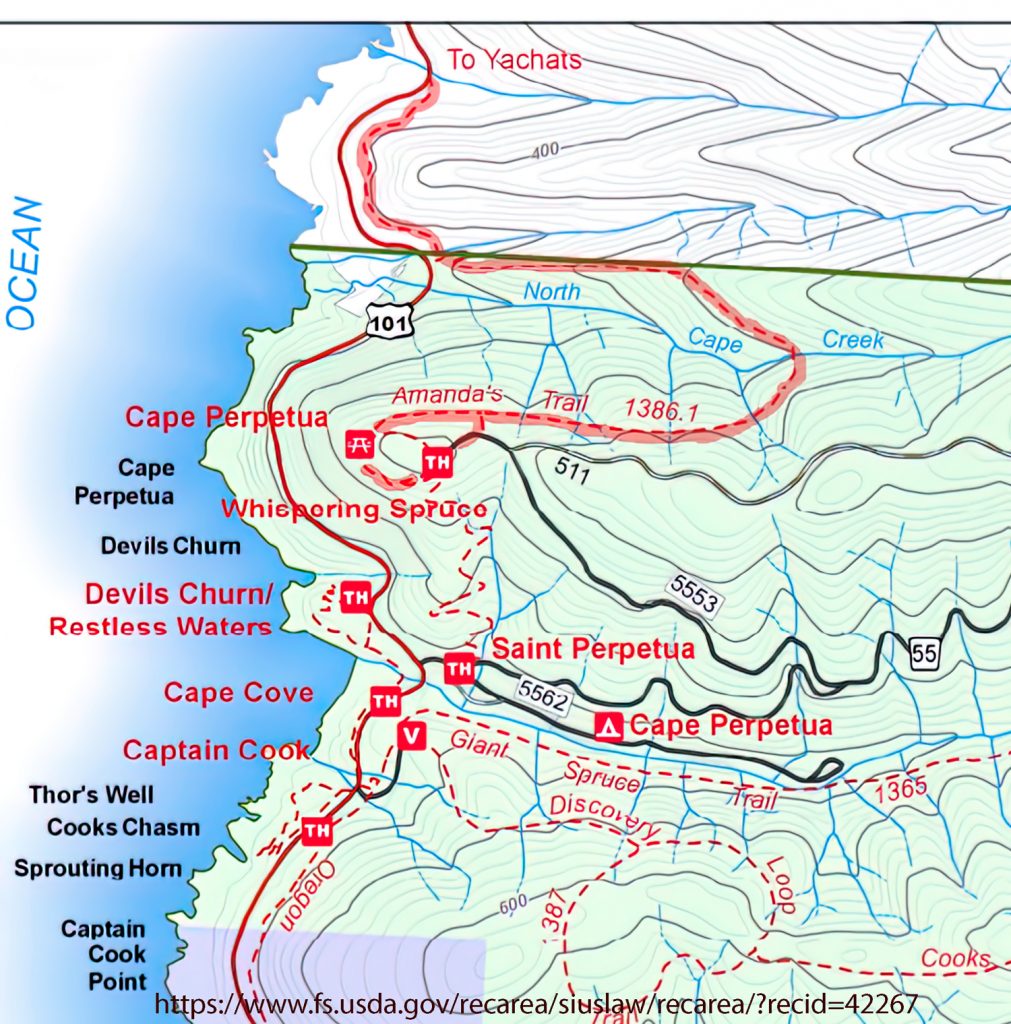

Amanda’s trail, a simple hiking trail that runs between the town of Yachats and Cape Perpetua’s stone shelter, is more than just a hiking trail. It has a soul and a story. It is good exercise, a nice day hike roughly paralleling highway 101 from Yachats to the stone viewpoint and shelter on Cape Perpetua, and it is a big step back into history and the story of one of Oregon’s many trails of tears.

Amanda’s trail, a simple hiking trail that runs between the town of Yachats and Cape Perpetua’s stone shelter, is more than just a hiking trail. It has a soul and a story. It is good exercise, a nice day hike roughly paralleling highway 101 from Yachats to the stone viewpoint and shelter on Cape Perpetua, and it is a big step back into history and the story of one of Oregon’s many trails of tears.

On October 14th, with our planned hike along Tam McArthur Rim in the Three Sisters Wilderness near Sisters, Oregon snowed out, we had to quickly make a change. My friend Mike suggested Amanda’s Trail down by Yachats, and I agreed. While we wouldn’t have snow, we could have a short period of rain which doesn’t require post-holing or snowshoes. Besides, it was someplace I’d been wanting to scout for winter storm photos. All that, plus being a much shorter distance to drive, and this trail sounded like a good trade.

Yachats Ocean Road State Natural Site is bordered by houses on one side, and the ocean on the other. This is a very different type of trailhead than we are used to. Normally we are way up in the hills, not in a residential neighborhood. There were no bathrooms, and no bushes or trees to hide behind. Normally, trailheads have limited to no views. Here, the ocean was gorgeous, and the waves were stellar.

The first quarter-mile or so follows the road, then we came to the trail itself. A dirt trail paralleled the western side of Highway 101 for a short distance, then crossed to the eastern side and climbed up the bank.

It was raining slightly still, but it was no big deal. We had raincoats, waterproof shoes, and high-tech quick-drying clothing. Our packs held light-weight high-calorie hiking snacks along with the emergency supplies we normally carry in the winter. Our cell phones had service and we could call for help if needed. The trail was well developed and easy to follow. Our gear was overkill for this hike, but it’s what we keep in our packs for the longer hikes out in the forest.

Flashback. 1864. You are blind or nearly blind. You are an older woman with an eight-year-old child. Armed soldiers are forcing you to leave your family and walk along this route to what to you is a prison. There is no well-developed hiking trail to follow.

No one in 1864 has any of the gear we carry regularly, and certainly not the Native Americans who lived on the coast. And certainly not one Amanda De-Cuys.

Little is known of Amanda De-Cuys, an old, blind Native American woman that the trail is named after. What is known comes from the journal of Corporal Royal Augustus Bensell who served at Fort Yamhill. This journal was published as All Quiet on the Yamhill: The Civil War In Oregon. Amanda’s story is one of the thousands of such stories as Native Americans in Oregon were rounded up and often forced to march great distances with little food and no support.

In 1855, President Franklin Pierce signed an executive order designating an area from Cape Lookout south to the Siltcoos River, and twenty miles inland as a reservation. Coastal Native Americans were forced to live there. This sizeable rugged area was of no interest to settlers at the time. However, the treaty was not ratified by Congress and none of the promises of food and supplies ever arrived.

Amanda’s trail parallels Highway 101 for a while, climbing up and down the bank, providing views of the pounding surf and the ocean. It crosses a couple of roads and passes through private land. Signs ask people to stay on the trail. Eventually, we reached a bronze statue of two black bears hugging which honors Norman Kittel. Norman and his wife, Joanne, were instrumental in finishing the trail and signed a permanent easement so it can cross private property.

Amanda’s trail continues to run through timber and parallels the highway until it reaches a stream crossing. Here, tucked back just off of the trail, is the Amanda Shrine. This serves to honor the life of Amanda De-Cuys and other Native Americans who were forced to walk this area. Many items were placed at the base and medals were hung from the statue and trees around it to honor her. A collection of rough benches were placed in an amphitheater arrangement where people could sit. There are historical and interpretative signs along the trail, and these tell the story of Amanda.

The rugged lands along the Siletz Reservation eventually became the target of settlers. At this point, troops were sent out to “round up” the Native Americans and remove them up to the sub-agency at Yachats.

According to Corporal Bensell’s account, his group traveled around the area, searching for Native Americans. They traveled up the Coos River and found the De-Guys ranch on May 1st, 1864 where they seized two women and a man. The corporal wrote, “We got two [women] and a [man]. After getting in the boat I was surprised to hear one of the [women] (old and blind) asked me, “Nika tika nanage nika tenas Julia [Let me see my little Julia].” I complyed with this parental demand and was shocked to see this little girl throw her arms about old Amanda De-Cuys neck and cry, “Clihime Ma Ma [dear mama].” De-Cuys promised the Agent to school Julia. We started back with the tide. Got home at midnight. Good night.

Since De-Guys had not formally married Amanda according to the customs for white settlers, she was forced to go with the soldiers and the Indian Agent and had to leave her young daughter behind. Many such families were torn apart.

The trail leaves the Shrine and crosses the small stream, then begins climbing. Soon the sound of traffic faded away and we hiked on good trail through the timber. The rain had stopped but there was still the sound of water dripping from the tree limbs. As we climbed we entered the fog which created a beautiful mistiness among the trees. The trail switched back and then we eventually reached a trail junction at the Cape Perpetua viewpoint parking area. We followed the signs and the trail swung around to the stone shelter. The low clouds and fog limited visibility. On a clear day, one can see a reported distance of 40 miles.

This shelter offers an amazing view and is more than worth walking out to from the small parking area. Since it was windy we opted to sit on the bench and have a snack. It was here we met the first people we had seen, three hikers who were coming from the other direction.

Amanda and the others were forced to walk 80 miles up to Yachats. When she crossed Cape Perpetua, she cut her feet badly enough to leave a blood trail. Corporal Bensell wrote, “Amanda who is blind tore her feet horribly over these ragged rock, leaving blood sufficient to track her by. One of the Boys led her around the dangerous places. I cursed Ind Agents generally, Harvey particularly.” Bensell’s account tells of conflicts with the Indian Agent and his being over-ridden by the Lieutenant leading the soldiers on multiple occasions. At one point the Agent wanted to leave the old women behind to die because it would cost too much to take them along. The Lieutenant objected. They took the women along.

The hike back went quickly. The first part was mostly downhill which made it easier. We met a few other hikers as we descended. Eventually, back at the parking area, I reflected on our walk. We had a groomed trail, high tech clothes, good shoes, and food. What did Amanda have?

This trail also left me thinking about the history I had learned growing up. Fortunately, Neah-Kah-Nie High School had required a class called Pacific Northwest History taught by an avid historian and teacher. Much of the history of the Pacific Northwest is glossed over in the typical high school history textbooks. Events like this are not considered of sufficient import to be included.

I highly recommend this trail. The hike is considered moderate and that is because of the long gradual uphill stretch. It isn’t too steep and there was very little mud. Proper trail footwear like trail runners or hiking boots would work just fine. We met a small group of people who were wearing regular street shoes.

The out and back route was 7.4 miles long. It is possible to park a vehicle at the top trailhead and hike the 3.2 miles down to another vehicle parked in Yachats for an easier experience. This would be an excellent winter hike. It would make for an excellent trip down the coast to sightsee and hike, followed by a dinner at one of the many restaurants along the way.

Unfortunately, the trail from Yachats to the Amanda Shrine is temporarily closed pending the installation of a bridge. The Forest Service posted this announcement: 8/30/2021: Portions of the Amanda Trail will be closed for construction of the suspension bridge at Amanda Creek & Gathering Grotto. People can still hike about 2 miles from the Overlook trailhead to the closure at the bridge construction site. The section south of the Amanda Statue will be closed between Oct. 1, 2021 – Feb. 28, 2022. No trail detour is available. The trail on the north side of the Amanda statue will have intermittent closures during this same period. The majority of the closed area is on private property on the north side of the trail.

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde have the following statement on their website. It partially reads:

Trail of Tears

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde were formed when the U.S. government forced member Tribes to cede their ancestral lands and created the 60,000-acre Grand Ronde Reservation in Oregon’s Coast Range. Beginning in February 1857, federal troops forced native people to march from a temporary reservation at Table Rock in southern Oregon 263 miles north across rough terrain to the newly created Grand Ronde Reservation.

Thus began Oregon’s “Trail of Tears.” The Rogue River and Chasta Tribes were the first to be removed from their aboriginal lands. They were joined by members of other Tribes and bands as the march passed other tribal homelands. The journey took 33 days and many died along the way.

George H. Ambrose was the Indian agent charged with carrying out the march. Historian Stephen Dow Beckham edited the agent’s 1856 diary “Trail of Tears.” He summarizes Ambrose’s writing saying the diary “hints at the dimensions of suffering and tragedy endured by the Indians of southwestern Oregon in the 1856 removals to the new reservations. Similar forced marches northward befell the natives of the Umpqua and Willamette valleys as well as several bands brought along the coastal trail from Port Orford to Siletz during the summer. ‘It almost makes me shed tears to listen to them as they totter along, observed Lt. E.O.C. Ord who witnessed one of these removals.

“Left behind were the bones of parents, grandparents, and ancestors, ages-old villages and fisheries, and a way of life well-tuned to the rhythms of a beautiful land.”

Sources:

Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde: Trail of Tears: https://www.grandronde.org/history-culture/history/trail-of-tears/

Oregon Hikers.Org: Amanda’s Trail Hike, https://www.oregonhikers.org/field_guide/Amanda%27s_Trail_Hike

Shichils Blog: Amanda’s and Bensell’s Diary: https://shichils.wordpress.com/2014/04/30/amanda-and-bensells-diary/

Trailkeepers of Oregon: Amanda’s Trail and the Forced Relocation of Oregon’s Peoples:

https://www.trailkeepersoforegon.org/amandas-trail-forced-relocation-oregon-peoples/