Story from the Barrier Miner – April 6, 1908 (Broken Hill, New South Wales, Australia article and found that they got the story from the “Daily Telegraph”)

Writing from Los Angeles (U.S.A.) on February 20, 1908 the correspondent of the “Daily Telegraph” says that nine

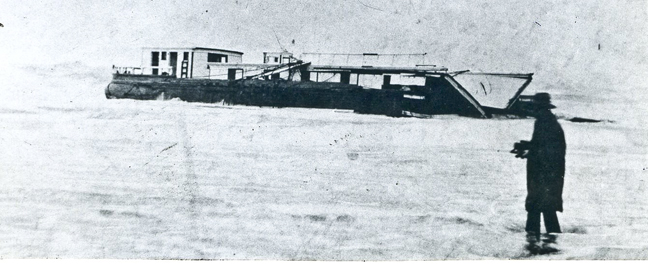

members of the crew of the American ship Emily Reed, 103 days out from Newcastle, Now South Wales, with a cargo of coal for Portland, Oregon, were lost when the vessel went ashore half a mile south of the Nehalem River, on the Oregon coast, at 1.30 o’clock in the morning of February 14.

The dead are ship’s Carpenter Westlund, Seamen Sortzeit, Johnson, Dickson, Darling, Cohenstad, and Gilbert,

the cabin boy (Hirschfeld), and the cook (name unknown). Captain Kessel, his wife, First Mate Fred Zube (or Dubie), Second Mate Charles Thompson, Seamen Ewald Ab Idstedt, Arthur Juhunke, Sullivan, Bartell, and Franchez were saved. The captain, his wife, and five of the survivors managed to make their way ashore when the ship struck, but the first mate, two seamen, and the cook were not rescued till they had voyaged 200 miles in an open boat. The cook died from the hardships he endured, and through drinking salt water, while the others were all delirious. The ship has broken up, and together with its cargo of 2110 tons of coal is a total loss. Owing to the long passage of the ship, 25 per cent. reinsurance had been offered on her. For several days preceding the wreck heavy weather had prevailed off the coast of Oregon. The main cause of the disaster, however, was the fact that the captain’s chronometers were wrong. Captain Kessell was endeavoring to make Tillamook Rock. He was correct

in his latitude, but too far to the eastward. When he discovered his position the vessel was among the breakers.

It was too late to wear ship, and she struck on one of the most dangerous places on the Oregon coast. When she

hit the beach bow on there was a heavy sea running and a strong flood tide. Her back broke, and the forward end

took a list to port. A lifeboat was launched, in which were the first mate, Fred Zube (or Dubie, he being given

both names), Seamen Ewald Abildstedt, Arthur Jahunke, and the cook. It seemed to the captain and the rest of

those on the wreck that, as soon as this boat hit the water it was swamped, and they so reported when they, reached

shore.

Three days later this lifeboat turned up 200 miles to the north. After having seen, as he thought, four of his men drowned before his eyes, the captain advised the remainder to stay by the wreck till daylight broke. He himself remained on the poop, but forced his wife to keep below. The second mate and three men on his watch were on the main deck. When the forward portion of the ship listed they succeeded in making their way aft, and clung to the ship till daylight, which brought dead low water, and then they, with the captain and his wife, managed to get ashore. The captain reported the death of 12 of the crew, but on February 17 came the report from Neah Bay, Washington State, that three more men had survived. Just about midnight the watch of the little six-ton sloop Teckla, lying at anchor at Neah Bay, was startled by a feeble hail. Those on deck saw a steel lifeboat drawing up slowly. The boat carried four men, three, living and one dead, from the Emily Reed, whose timbers were being pounded on the shore of Oregon, 200 miles away. The cook had been dead over a day, while the first mate and the two seamen with him were in a pitiable condition. Their tongues were so swollen from thirst that they could scarcely articulate.

Later in the day the first mate was sufficiently recovered, to be able to tell

their story. “Almost the instant the Emily Reed struck the beach,” he said, “she began to break up. As she struck the spats went out of her. We had scarcely a minute’s warning of breakers before the shock came. I was forward, calling all hands on deck when she struck. In a twinkling one of the lifeboats was smashed by a big wave, and the decks were so deep in the boiling water that there was no time to get aft, where Captain Kessel and his wife and some of the rest of the crew were. “We had to act quickly; Abilstedt, Jahunke, and the cook came tumbling out of the forecastle with scarcely any clothing on their backs. We jumped into the remaining lifeboat and cut at the lashings. A big sea broke over the wreck and carried us clear. A second wave carried away, part of the galley deck roof, and it was hard work clearing the boat of the wreckage. One of my arms was broken when the wreckage of the galley dropped on to us. Moreover, there was only one good oar in the boat. We did our best to get back to the wreck, but failed, and, believing all hands save ourselves were lost, we got up sail and stood out to sea. As I knew the coast to be a desolate one, I thought it best to keep the boat well out, hoping to fall into the path of steamships. With this idea I set the course northward. “Water came in fast, as the metal boat had been punctured in several places by the wreckage which fell on her. There was nothing to bale with so we tried to cut off part of the air-tight compartments with our knives. It was tedious work sawing at the tough metal, and we had worn all our

blades off before we could wrench half it off. “This box we used as a baler. It took about half an hour to get the boat empty, and in about half an hour we would have to do it again. The second night out we saw lights ashore,

but it was too dark for us to venture in. There was neither food nor water, and we suffered terribly from thirst.

Toward evening the cook declared he could not stand it any longer, and took a drink of sea water. He soon became

delirious and lay down in the pool of water in the bottom of the boat About 2 o’clock Sunday morning we saw a big

steamer. She stopped near us, and we believed we should be saved at once. One of the men shook the cook awake, and, pointing to the steamer, asked him if he didn’t want to be saved. He got on his feet and seemed rational as he watched the steamer. Just then the vessed got under weigh again and left us. Then the cook gave up the fight. He lay down to die. Half an hour later we found his body cold; his heart had stopped beating. “All Sunday we kept seeing all sorts of vessels, but none would answer our hails. I suppose we were too far off to be made out plainly. When we sighted Tatoosh lighthouse at night we gathered what little strength we had left and steered the boat to Neah Bay.”

The little boat was at sea 78 hours, and must have drifted at the rate of two miles and a fraction per hour to

get 200 miles north. There was a biting wind most of the time, and the men suffered terribly from exposure as

well as from want of food and drink. The Emily Reed was built in 1880, belonged to Hind, Rolph., and Co. of

San Francisco, and left Newcastle, New South Wales, for Portland on November, 3, 1907.