by Neal Lemery

“We are collections of stories, we are vast houses in which stories come and go, and if we don’t listen for them, and savor them, and carry them in our pockets, and share them, then we have nothing, for stories are compasses and lodestars… stories are how we live.” –Brian Doyle

I’m a collector of stories, stories from family, from friends, from my own adventures and experiences in life. Every day, I experience a story, and probably a lot of stories, if I pause to think about the day, and what has occurred, what I’ve seen and heard and felt. Stories are all around me.

Sometimes, I’m aware enough to realize that I am, indeed, experiencing something special. I need to capture that, before it moves on, and leaves me wondering what I experienced, and if it was worth remembering. I often leave the good stories, the gems of the day, on the side of the road of life, thinking that it wasn’t worthy of my time. But if I think about it, those are often the gold in the day, stories that need to be told. They have value in being remembered and shared.

Stories sometimes are incomplete and need to be added to in order to reveal their true mystery, their complete wholeness. In that new retelling, with new details and plots, the story truly shines and becomes even richer in our lives.

When I was a kid, my family would tell the story of my great uncle, who was a dory fisherman on the Oregon coast. In 1913, he drowned, and his body was never found. It was a tragic tale that my grandmother would retell every Memorial Day, when we went to the old family cemetery to tidy up the graves and lay some flowers from her garden.

She would tell the story as we picnicked at the cemetery, after our work was done. She’d point to Uncle Guy’s gravestone, and tell us he was a handsome man, a good man, a teller of jokes, and that they never found his body. His parents put up the headstone, giving him a place among the family members who had died. That act of placing the headstone gave them some peace, and a place to come to and mourn. He was only 26.

It was a sad story, but also a story of love and family, a story that gave some meaning and peace at our Memorial Day tradition.

A month ago, the story took on an added dimension. Out of the blue, my e-mail box had a message from someone in Indiana, inquiring whether I was the son of my mother, and that the writer had discovered some family letters I might be interested in.

We began a vigorous correspondence, and I learned that great uncle Guy did not die alone, but was with his friend from Indiana, and another fisherman, and that the friend had drowned alongside my uncle, that neither body was found. The survivor made it to shore, reporting that a sneaker wave had capsized them on an otherwise calm February day, near Haystack Rock, by Pacific City, Oregon. The survivor did all he could to save the other two, but they all grew cold and weak, and he had to swim to shore to save himself.

The letters were written by my great grandfather, telling the Indiana family of my uncle’s friend of his death, of not finding the bodies. There was mention of his steamer trunk, and that my grandfather was going to send it back to Indiana, so the family could have some solace, some tangible memory of their beloved. The man had left his wife and children and had traveled to Oregon, and much of the last part of his life had remained a mystery to the family.

They were curious about the deaths and the tragedies, and so I told them the stories of my grandmother, and the stories I knew about the perils of being a dory fisherman, the unpredictability of being out in the winter ocean in an open boat, powered only by oars, and not wearing life jackets.

I found newspaper articles that told the story, briefly mentioning the inconsolable grief of my family. My new friends in Indiana had scanned the letters of my great grandfather. I recognized his handwriting, from my childhood times of looking at old family books and cards. I could see how his hand trembled from grief over his son, as he told the stories of how they searched the beaches for weeks on end, how the oars had floated onto the beach, and how they yearned to find the bodies, to no avail.

Other family conversations now made sense to me, including my grandmother’s and mother’s avid admonitions to wear life jackets when we went boating. No one had made it clear to me the connection of Uncle Guy’s drowning and not wearing a life jacket, and the family mandate about boating safety and precautions.

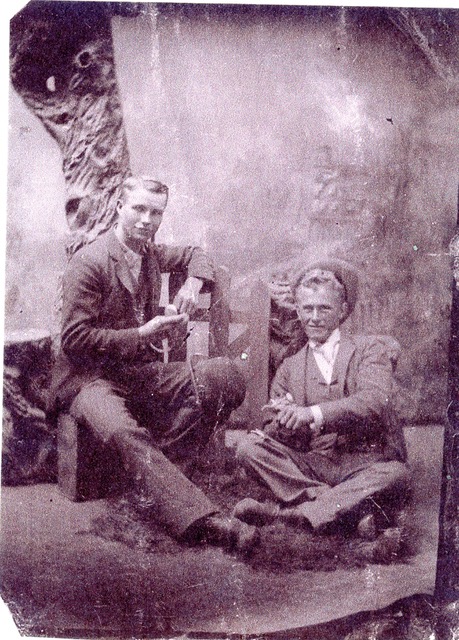

In Indiana, that family had talked about their son and husband, the substantial amount of money my grandfather had arranged to send them from Uncle Guy’s friend’s bank account in Oregon, and the arrival of the steamer trunk my grandfather had sent. The trunk is still in the family, and was a safekeeping for my grandfather’s letters and the studio photo taken of the two men a few weeks before the ill-fated fishing trip.

A copy of that photo was on my grandmother’s dresser all the years I knew her. I realize now that her copy was edited, omitting the friend, and only showing the stern face of my great uncle. As was appropriate for the times, he was formally dressed in a vested suit and tie, and not in the canvas pants, wool shirt, and rubber boots of a fisherman.

Now, I have more questions for my grandmother, but she passed on many years ago. Like so many stories, the telling raises more questions to be asked. Many may never be answered, that silence adding to the mystery of life and the need to be the methodical storyteller.

Both families now have better stories to tell, with more details, more complete about the loss that devastated so many back in 1913. I think I know my great uncle a little better, the stories of my grandmother now fleshed out. The family story is richer now, more complete.

I now have my own copy of that photo, the complete one, of two good friends who were going to go fishing on the ocean in February. I look at their faces, part of me yearning to sit down with them after their day of fishing, and tell me the stories of their lives.