EDITOR’S NOTE: From Nehalem Bay State Park – There has been an uptick in dog-walking traffic within the Snowy Plover Management Area. Locals and visitors are asked to refrain from intruding on this sensitive area. There has been quite a bit of work to encourage the return of breeding habitat and provide these federally-protected, endangered birds a safe space for this part of their lifecycle.

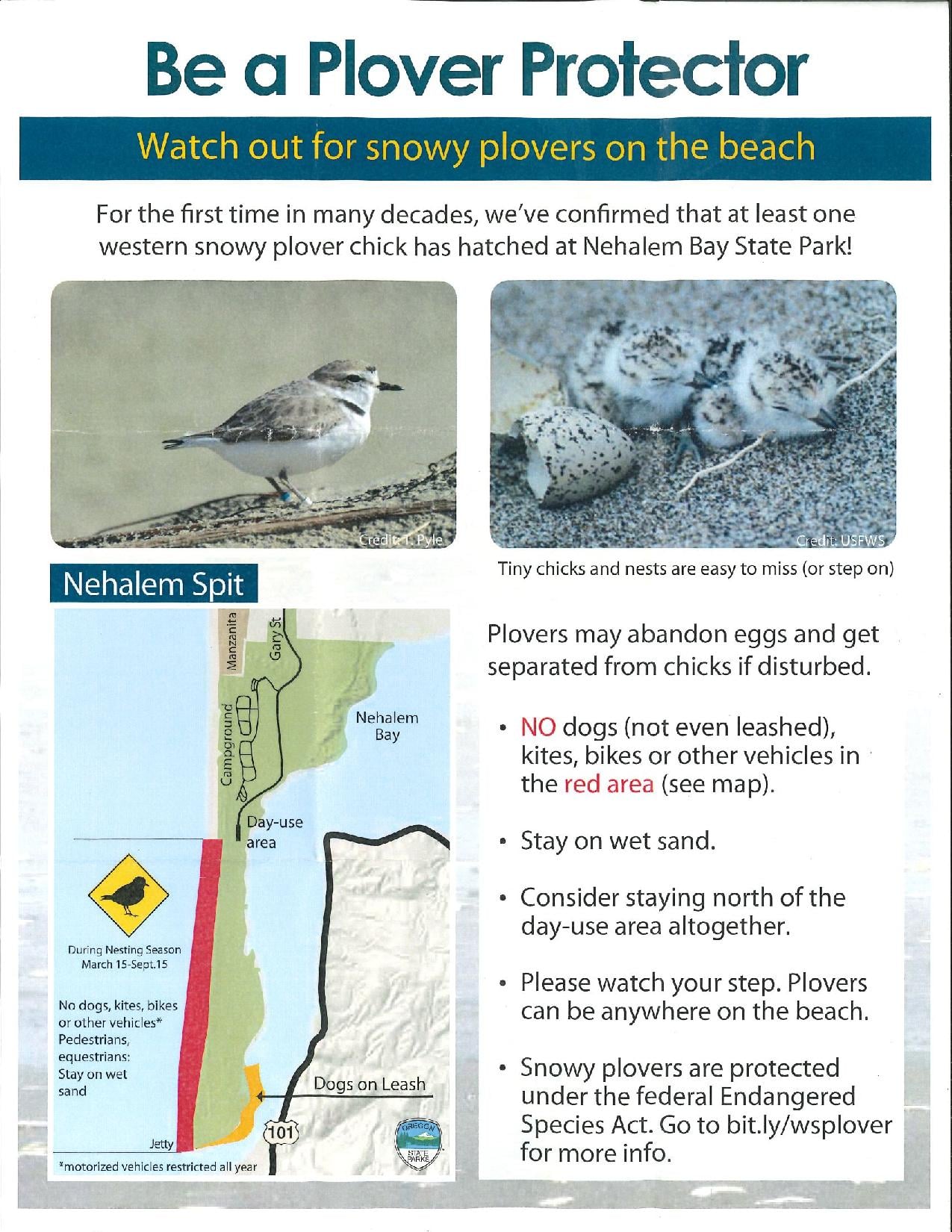

Please respect these efforts – and avoid a potential hefty fine for violating the SPMA rules. Be “bird-aware” and when on the south Nehalem Spit area, dogs are not allowed at all, not even leashed within the SPMA; people (and horses) are allowed to walk on the wet sand area only – for more details see the flyer below.

By Cara Mico

The Western Snowy Plover has finally returned to Nehalem and the Portland Audubon Society along with the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department (OPRD) wants you to exercise caution when visiting particular areas of Oregon’s beaches this summer. When on the beaches look for signs surrounding the plover habitat recovery area. In Nehalem, you can’t miss it. Unless you are a volunteer for the Audubon Plover Patrol program, or on horseback, the dry sand beach south of Manzanita is closed for a small distance on the southern spit. Don’t worry, you’d have to walk a really long way to get there. It’s much closer to the Nehalem Bay State Park campground, so if you’re camping in the park, stay on the marked trails, stay on the wet-sand, and keep your dog out of conservation areas. All the beaches for the Snowy Plover Management Area (SPMA) are signed at each entrance with big yellow diamond signs.

The plover is known to many Pacific Northwest bird enthusiasts as a tiny shorebird that used to flock in large numbers on Oregon’s wide, sandy beaches during the summer to nest in expansive dunes. The plover, like many on the US federally threatened species list, experienced massive declines as humans increasingly encroached upon their territory.

European beach grass planted to stabilize the dunes lead to a decrease of nesting habitat. Fewer birds being pushed into smaller spaces lead to an increase in predation. Predators such as coyotes and raccoons have an easier time reaching plover nests, taking easy advantage of human-made infrastructure such as roads and bridges. Crows and ravens will watch humans, coyotes, and other mammals, follow these hunters to plover nest sites. Coupled with human disturbances such as joggers, dog walkers, and party goers and plovers faced an uphill battle.

The biggest threat that plovers face? Their eggs resemble small rocks the color of sand. Unless you know what you are looking for, and where to look, they are nearly invisible. Nest trampling is one of the biggest challenges in the effort to recover the plover species.

This is a large part of the habitat conservation plan which was developed by the OPRD to increase plover populations. Audubon took over part of this management plan in 2018 to assist an already understaffed parks department, a role which has increased as the OPRD faces even more massive budget cuts due to the pandemic.

There are 4 SPMAs in Oregon, protected from disturbances with fences and signage, and they are monitored by a group of trained volunteers who count the number of birds present, the location, and information about nests. On the Nehalem spit part of the plover management plan includes removal of invasive non-native beach grasses which prevent natural dune migration and replacement with native grasses which help to build up a wider foredune where animals like the Snowy Plover nest. So far recovery efforts in the state are proving successful, although it isn’t clear what the future of the plover holds as climate change is also a factor in their overall success.

Allison Anholt, the Coastal Bird Coordinator at the Portland Audubon, manages the plover SPMA in Nehalem, as well as the Plover Patrol training program. “Volunteers count and look for plover bands during low tide, they aren’t disturbing the nest and they get a good understanding of what birds are migrating and why, these are really important questions that science can answer. Volunteers need good eyesight to see the birds, be careful observers, and doesn’t mind being out on the beach for a few hours at a time,” said Anholt during a recent interview.

If you want to volunteer, the Nehalem dry-sand volunteer season is May through July. You will need to wait until next March to get trained and on the permit. You can get trained this year however to volunteer for the wet-sand surveys. You can also join the next Nehalem interpretive walk on June 19, email Allison or go on Audubon to RSVP.