By Cara Mico, Assistant Editor

You may have seen the lines of immigrants arriving daily in Texas, New York, and California recently in the news. I’m going to be looking more deeply at this issue, including taking a trip to border towns to interview the people looking for a new life here in the United States to better understand their plans, motivations, and to provide insight into this sensitive topic. This article doesn’t reflect my opinion, and I’m working on providing objective information. This is part of an ongoing series and by no means is meant to encapsulate the entire topic in one brief.

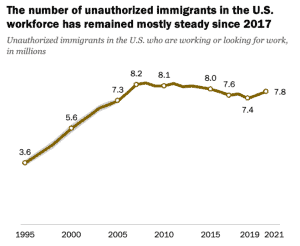

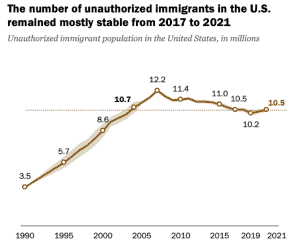

While some have claimed that immigration has gone up because of Biden administrative policies, when you look at the data, this isn’t likely the case when considering macro trends. The number of unauthorized immigrants in the US peaked in 2007/2008 and has been slowly declining since then. The number of unauthorized immigrants currently living in the US is about the same as it was in 2004.

For those who believe a wall is the solution, during the Trump administration when immigration and new visas were scaled back and border security increased, this population only fractionally decreased suggesting these policies have little impact on the flow of unauthorized border crossings.

This isn’t to dismiss the problem, certainly the recent increase in unauthorized crossings is concerning, especially given the massive increase in fentanyl trafficking, there are clearly larger macrotrends driving this immigration.

Unauthorized immigration has been rising steadily since the early 90s. Recapping common arguments both for and against unauthorized immigration (we’re not including legal immigration in this discussion), those in favor believe that open borders are a human right, that the US is a colonial state and has no right to keep anyone out, and that there aren’t enough citizens to fill the open low-skill labor positions. Some even argue that increasing the number of low-skill laborers keeps inflation at bay. Those opposed often cite national security risks, decreased opportunities for citizens, voter fraud, and a drain on resources for those citizens most in need.

Given the breadth and scope of arguments both for and against, I’ll start with the simplest argument to tackle. The most common argument in favor of increased immigration, unauthorized or otherwise, is that the US doesn’t have enough workers for farming. We can pull some basic statistics to see if this bears weight.

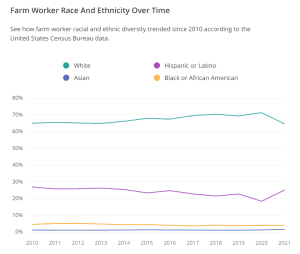

Most farm workers within the US are white, except for the state of California where most are non-US born Latinos. Figures vary but somewhere between 60-90% of California farm workers are Latino with a small percentage of those being born in the US. This makes sense given the large number of Latino residents in the state as compared to the rest of the US. Perhaps surprisingly, when you look at agricultural worker demographics, they largely match the demographics of the nation for race.

There was a marked increase in Latino agricultural employment matched by a proportionate decrease in white agricultural employment over the same time period. Although California hosts more total farm workers, 30 other states host a larger percentage of farm workers and the majority of those farm workers are white, and natural born citizens. So this argument that white people aren’t willing or able to do these jobs isn’t accurate. In fact Texas has more agricultural workers by totals and by percentage, the majority of whom are white, followed by Latino, then Black.

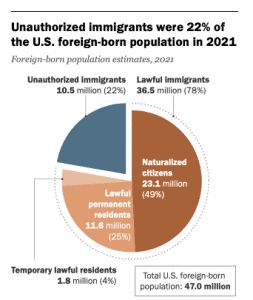

Another aspect of the debate is that there isn’t enough legal immigration to supply the labor demand. The facts don’t support this argument either, with the majority of immigration being legal. In fact, almost 50 million US residents are foreign born with fewer than 11 million unauthorized residents.

From an economic perspective this is a challenge since social services are already strained to the level that many citizens who need social services are denied or put on years-long wait lists for disability or affordable housing. This is also problematic since the rate for social services is higher for unauthorized immigrant populations than for non immigrant populations. This puts strain on a system that is essentially a pay-in fee for service. Meaning that there is an expected rate of social service need within a population, that population is taxed for this service with the expectation that the rate will stay relatively stable. So if the population needing these services increases amongst a group that hasn’t paid into the system prior then that means there are fewer resources for those who are already here who need them.

When you look at the current estimates for unemployment, there are just over 6 million unemployed working age people who are still looking for work and there are about 8 million unauthorized migrants in the US workforce, many of whom are employed as seasonal agricultural workers, which has one of the highest unemployment rates in the US.

How do we make sense of this data?

Let’s look at the economic systems that brought us to this point. In the face of economic challenges in the 1970s and 1980s, the global economy saw a decline in the agricultural sector, prompting countries like the U.S. to cut food import tariffs. This, alongside the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), led to a complex web of consequences, including job losses in some sectors and a less sustainable farming environment in Mexico and South America.

NAFTA aimed to eliminate trade barriers, promoting capitalism and stability to counter communism. The U.S. has historically opposed communism, engaging in actions like the McCarthy era and the Vietnam War. By establishing free trade with its neighbors, the U.S. sought to create a prosperous North America resistant to communist influence.

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), a group of indigenous Mayan rebels in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, launched an armed uprising against the Mexican government on the same day NAFTA came into effect. They argued that the trade agreement would have negative effects on the rural poor in Mexico and lead to the privatization of communal indigenous lands, which would then be sold off to foreign investors.

As a result, unauthorized immigration from these regions has surged, driven not only by economic factors but also by poverty, political instability, and violence. Understanding these intricate connections is vital in tackling the challenges of immigration and trade, as we strive for a more balanced and fair global system.

While it is true that the economic challenges of the 1970s and 1980s, the reduction of food import tariffs, and the implementation of NAFTA in 1994 had significant impacts on the global economy, the agricultural sector, and job markets in Mexico and South America, there are other factors that may have contributed to the surge in illegal immigration.

The economic downturn in the 1970s and 1980s was not solely responsible for the decline in the agricultural sector. Other factors, such as technological advancements and the shift towards more efficient and industrialized farming methods, also played a role.

The impact of NAFTA on job losses and a less sustainable farming environment in Mexico is not as clear-cut as it may seem. While some industries and sectors may have experienced job losses, others may have benefited from increased trade and investment opportunities.

Economic factors, poverty, political instability, and violence have undoubtedly contributed to the surge in illegal immigration. There are other factors at play, such as the demand for cheap labor in the United States, the impact of globalization and trade liberalization, and the role of U.S. foreign policy in Latin America.

While the economic challenges of the 1970s and 1980s, the reduction of food import tariffs, and the implementation of NAFTA in 1994 have had significant impacts on the global economy and the agricultural sector, there are other factors that may have contributed to the surge in illegal immigration. Understanding these complex and interconnected factors is crucial in addressing the challenges of immigration and trade in a balanced and fair manner.

Does the data support the argument that Mexican immigrants have increased economic opportunity?

That’s a difficult question to answer. After the implementation of NAFTA the formal unemployment rate in Mexico dropped by half. But the unemployment rate of migrant laborers increased within the US. This suggests that the unemployed shifted locations, meaning that those who were struggling economically in Mexico moved to the US to look for work, but that a percentage of those couldn’t find stable employment and instead relied on social benefits.

Clearly this isn’t a simple issue, for instance we’ve also seen massive economic growth in the same time period from automation, the development of new technologies, and increased access to those technologies and education.

Further, for the first time in decades, the majority of foreign born migrants living in the US are not from Mexico, but rather the collective are from Central and South American Countries, the Middle East, and East Asia.

But just looking at the numbers, the argument that we need illegal immigration to support our agricultural system isn’t true. Not only are there plenty of unemployed agricultural workers already here in the US that could fill these roles, but that the root causes that drove people to immigration in the first place may be damaging the long-term stability of the countries from which they are leaving.

Food for thought. Stay tuned for an update when I take a trip to the border to interview people in the area, both foreign born, and citizens, to get a better idea of what’s actually happening on the ground. Please provide feedback! If you have experience in the agricultural community or in immigration policy I want to hear from you!

*Data for this article was obtained from Pew Center for Research, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security, Zippia, Statistica, and the National Center for Farmworker Health as well as the Bureau of Labor and Statistics.