EDITOR’S NOTE: The Tillamook County Pioneer posted Miel Macassey’s support for Erin Skaar and David McCall with information about the Tillamook Lightwave project last week; and then on Wednesday May 13th, Commissioner Yamamoto took the opportunity to “campaign” about his work on this much needed communication network, which was an inaccurate representation of his participation in the process. Miel Macassey’s follow-up Q&A below provides details about the backbone system that has been available, but has remained essentially under-utilized while areas of our county do not have equitable communication capabilities.

From David McCall, Candidate for Tillamook County Commissioner Position #2:

I was surprised to hear Mr. Yamamoto’s “report/update” during the televised Commissioners’ Meeting Wednesday. I am quite pleased that he was able to advocate for the same “mesh” system which I outlined in another local news interview last week, as well as to Oceanside residents the week before. It is an interesting coincidence that this news comes during a campaign, and while it may indeed be the culmination of several years’ of research and development, credit should be given to those who are making this possible:

Julian Macassey has been attending TLW meetings and pounding this home for over a year now;

Julian and his team were able to involve Rep. Tiffiny Mitchell, who educated herself and convened this meeting on Tuesday, at which the grant opportunity was laid out for Mr. Yamamoto;

Senators Merkley and Wyden announced funding to aid such efforts this week.

Whether this was a campaign stunt or not should not be an issue. The important thing is that as a result of these meetings and announcements, affordable, high-speed Internet will be available to Tillamook County residents by the end of summer, without regard to the outcome of this election.

The groundwork laid out through the formation of TLW, as well as the opportunities facilitated to us by one our local representatives and our two Senators have come together to benefit the communities of Tillamook County.

By Miel Macassey

What does Tillamook Lightwave do?

A partnership between Tillamook County, the Tillamook People’s Utility District, and the Port of Tillamook Bay. They own a landing for two transpacific communications cables in Pacific City, a high-capacity fiber-optic backbone within the county, and operate a local publicly-owned broadband network.

Wait, what? We have a local publicly-owned broadband network?

Yup.

TLW installed the main trunk of fiber 15 years ago. It is under the white and orange poles that you may notice as you go down the 101 and along some other roads.

The Federal and State grants that paid for that installation began with Clinton Administration grants to hook up public services and were intended to create a network that would be extended to homes and small businesses. TLW stopped when they completed the mandated connections to emergency services, government offices, schools and libraries, and when they hooked up 24 of the biggest commercial accounts in the county.

I live near a white and orange pole! Can I just get a TLW account and zip off onto the information superhighway?

You would have to pay for an individual installation under what is called fiber-to-the-home (FTTH), which is prohibitively expensive for most mere mortals. You would also have to serve as your own internet service provider. TLW could have used economies of scale to hook up a neighborhood at a time as funds became available, but have not.

FTTH costs an average of $138,000 per mile for trenching it underground. Aerial (hanging it from TPUD or other utility poles) is a bit cheaper at $56,000 – $58,000 per mile. You be the judge.

How can Dave McCall and Erin Skaar promise to quickly provide broadband internet when Tillamook Lightwave has not done so in 15 years?

Through a combination fiber-mesh network.

Ok, I get the fiber part. What is a mesh network?

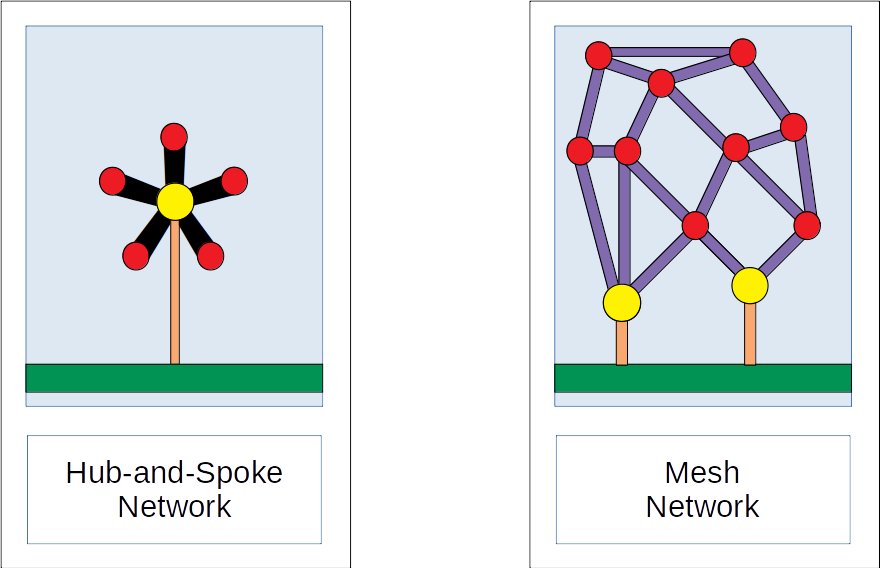

Traditional networks, whether DSL, cable or telephone, use a hub-and-spoke system: one central point handles all signals to and from each endpoint. This is most efficient when trying to minimize the amount of trenching and cable needed, but it leaves two central vulnerabilities: the loss of the center takes out everyone, and endpoints have no redundancy on their individual spokes. Each node has only one route to the rest of the world, and it can go down in multiple ways.

A wireless mesh network has multiple nodes that branch off of the main network and those beyond them can talk to each other, relaying signals so that if one connection goes out, another is available. It is most often done with beams of radio waves tightly focused between two points, rather than broadcasting in every direction like a radio station transmitter, and uses different frequencies.

One of the features it offers that other modes do not is that, should the trunk line go out, the mesh would still allow those on it to communicate to one another. This was done after Hurricane Sandy by the Red Hook Initiative in Brooklyn, which had been providing a local mesh network before the hurricane. After, they offered a local network and public wifi even when residents had no internet access, electricity or water.

Is a mesh network as good as fiber?

In terms of speed and resilience, nothing is as good as fiber. Mesh is not measurable in the same way as wired services because speeds vary greatly depending on the number of nodes and their configuration, but all mesh networks go onto the fiber backbone. Since the speed of fiber is so much higher than other options, the combination is still going to be faster than a wired method would be if commercial services extended to the same place. Long cables have attenuation, too, and the fragility of a long hub-and-spoke system over rugged terrain is significant.

A factor with mesh, as with any wireless network, is that the signal is more affected by weather and changes in the environment. There must be clear line-of-sight between nodes.

Who else is doing this?

There are rural and urban networks around the world. In Oregon, Clatskanie has a very innovative one called Althea Networks that also deploys mesh networks for emergency response and has recently installed a long-term, permanent network in Garki Abuja, Nigeria.

The municipal network of Sandy, Oregon, is also a mesh-fiber network managed by their public utility district.

It sounds interesting, but can’t we just put in fiber?

That is the plan! Putting in mesh takes far less time and money, so it can connect us when we need to be staying home. Then we can start putting in FTTH using economies of scale. Some more isolated places may do best on mesh instead of fiber in the long term, but it will still be better than a commercial provider would offer the same location.

That seems like a lot of work. Won’t it cost a lot of money?

There are funds for doing this right now from emergency grants, as well as more regular funds intended to bring rural areas up to the levels of service expected in suburbs and cities. Mesh is incredibly cheap, and the accounts who are hooked up first immediately begin to fund the next steps in the expansion.

The money is invested largely in labor. This means good, long-term local jobs for both the already skilled and trainees who can become professionals in this exciting, future-oriented career. Good telecoms technicians can take their skills anywhere (though we hope that they will stay with us, of course!).

Great! Where do I sign up?

The first step is to elect County Commissioners who support an extension of this public resource: Erin Skaar and Dave McCall. The backbone is a big, fat pipe to the internet that their opponents would hand over to a private operator under a no-bid contract and lock us all into for-profit monopoly for possibly decades to come.

It is time for TLW to fulfill its charter to wire up the people and small businesses of Tillamook, rather than offer only bespoke broadband for high-end customers.