By Neal Lemery

He didn’t quite make it to the median age of men who die from alcoholism in this country. He was only 45, and the average age of men dying from alcoholism is 47.

147,000 Americans die each year from alcohol disorder, the medical term for alcoholism, three times as many men as women. That’s 488 a day, and in Oregon, that’s nearly 2,200 a year. Alcohol disorder cuts twenty-five years from the normal lifespan, and 2% of those deaths are young people under the legal drinking age of 21.

My relative isn’t a statistic to me. He died a few weeks ago from alcohol poisoning, the effects of kidney failure and sepsis of the spleen. Finally, when he lapsed into a coma, his heart and lungs failed, as they weren’t able to function anymore without his daily intake of a fifth of hard liquor. His last day was spent being life flighted to a hospital and put on an intubator, giving his family a few short hours to say their final goodbyes.

He was a good kid, who I watched grow into his manhood, becoming a loving husband and father, a hard worker respected by his co-workers and his community. He was known for his laugh, his joy in singing karaoke, his love for practical jokes, and his rich sense of humor, for his love of nature. I remember his childhood enthusiasm for life as he would jump for joy and shout the name of his favorite superhero.

He was my superhero, a loving spirit, the embodiment of a fun loving and compassionate guy, someone so easy to love. And I’m already missing the second half of his life.

We only spoke of his drinking a few times. He assured me, he “had it under control” and it wasn’t a real problem. And, we lived far apart. I missed out on being able to see the warning signs, to perhaps intervene, to take him to get the medical care he so desperately needed near the end of his too short life. I’m struggling with my own “coulda, woulda, shoulda” thinking.

Now, I regret I didn’t speak louder, that I didn’t see the train wreck happening, that maybe I could have “done something.” Yet, he chose to drink, to keep the worst of it hidden, and that’s what a lot of us do. We try to fit into society, to conform, to be accepted. Drinking and drugging are part of our culture, accepted ways to cope with life, anxiety, and stress.

All that is part of our coping with mental health worries, and so we self-medicate and deny the elephant’s presence in our living rooms. We seem to ignore that help is available, as close as a phone call to “988” or even coffee with a good friend.

The family gathered last weekend for his celebration of life. His life was filled with good times, rich stories, and people who adored him. I cried during the slide show of the highlights of his life, remembering his respect and compassion for others, mourning that his life was cut too short by booze.

Like most families, booze is one of our addictions, one of the poisons that finds its way into family gatherings, slowly sowing seeds of destruction and dysfunction. I’m old enough now that I know most of the family history and the stories, across generations, of addiction, chaos, and early death.

Those statistics I found are personal and real. They are one way of telling the story of intergenerational trauma and abuse, genetic forces and expectations, and a story of society’s obsession with medicating our emotional pain, our loneliness, with what many of us think of as “having a good time.”

I have a high school reunion coming up this year, and, true to form for our class, it will be at a bar. I’m sure a lot of people will order a round or two, some will get drunk, and I’ll be pressured into having a drink and to be part of the old gang. Some of our class won’t be there, dying early, often from the effects of alcohol. A few in our class didn’t make it even as far as graduation, killed by someone drinking and driving.

Like most gatherings, my family’s celebration of my relative’s short life involved some drinking. His brother was sucking on a beer, and I took the opportunity to have a serious conversation. We got to the heart of it, and he heard my concern for his choices. It was time I spoke up and used my serious voice, to make the message loud and clear.

The lyrics of one of the songs chosen at the family karaoke lauded a man who drank himself to death, with the third verse telling the story of his widow’s death from drinking. Not too many people seemed to notice the disconnect, the irony, and the telling of the wrong message on a sad day. Yet that disconnect is part of our culture, part of our collective willingness to self-medicate, to choose numbness and booze to deal with our grief, our pain, our “dis-ease” at the way we live.

The lessons from this month’s family tragedy are still being learned, still being sorted out. I’m more aware now, less tolerant of turning away, ignoring the signs of addiction, of a cry for help, the opportunity to speak up and make myself heard.

When I hear the alarm bells, I hope I’ll speak up, offer a hand and a willing ear, and try to make a difference. It is the least any of us can do.

Books: NEW book – Building Community: Rural Voices for Hope and Change; Finding My Muse on Main Street, Homegrown Tomatoes, and Mentoring Boys to Men

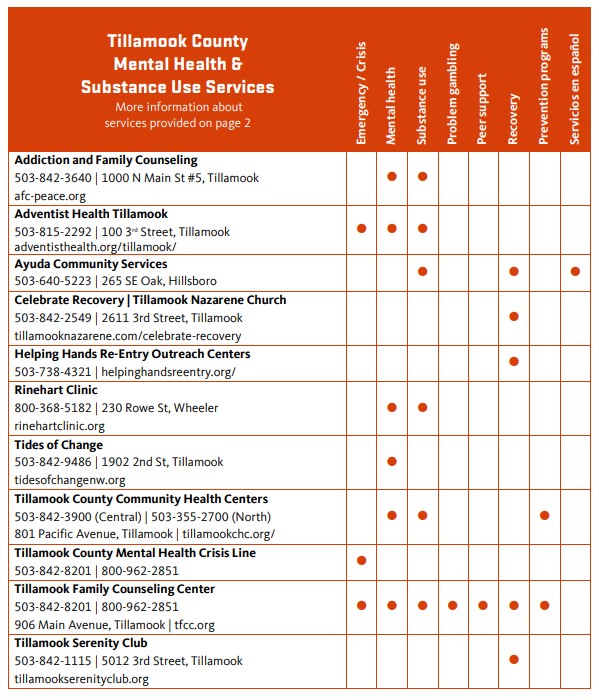

If you or someone you know needs help, there is hope – here are resources available in our community: