By Neal Lemery

Planting trees has always been one of my favorite things to do. I was probably three or four when my family took me out to plant trees. We had a cabin in the midst of the Tillamook Burn, an enormous part of the north Oregon coast range, which had suffered a series of devastating forest fires over twenty years.

The area had been mostly salvaged logged, and there were vast tracts of forest land with blackened tree snags, barren of living trees, and starting to be regrown with bracken ferns, grass, and brush. The periodic forest fires had ravaged the new young Douglas firs that had sprouted, leaving the hillsides denuded of its forest.

My dad had a big gunny sack of Douglas fir seedlings he has received from the local state forest office. We set out with a shovel and what he called a Pulaski, a wooden handled tool with a metal head that was an axe on one side and an adze on the other. One used the adze as a grubbing tool, and the axe head to clear brush and chop away the remnants of burned trees.

We set to work, me locating the places to plant and clearing away sticks, and my dad doing the axe and grubbing work with the Pulaski. We dug a hole and I placed the bare roots into the soil, pushing in the soil that we had dug. My dad tamped down on the roots with his boot. We made sure the roots were straight down in the hole and that the top of the roots were covered with soil.

There was a big discussion about “J- rooting”, which was a peril for the young trees. You didn’t want the roots to be curved, so that the bottom of the roots pointed towards the surface, as the tree would die. The roots needed to go straight down, and to grow into the water table, so as to survive the dry summers.

We’d visit the trees every few months. Checking on them, clearing any brush that grew nearby, and also replaced the few trees that had died, or that the deer had pulled out of the ground.

As a grade school kid, I had played a very small role in replanting the forest, going out with my classmates in a school bus, and planting seedlings for a day several times in the early spring. Our teacher and a friendly forester explained the workings of the forest and its importance, and how to plant the trees so they would thrive and start a new forest.

Over the years, the trees grew taller, filling in the landscape, and becoming a young forest. About ten years later, my parents sold the cabin, but I still drive by and notice the forest, now “middle aged” and on its way to becoming a mature forest. The area has changed so much, from a barren, blackened scene to hillsides of thriving green trees. Some have grown enough that they have been thinned and even harvested by timber companies.

What was the “Tillamook Burn” is now called the Tillamook State Forest. Revenues from timber sales enrich the state treasury and provide income for the local school district and the county.

In my adult years, I still plant trees. Like my grandmother, I like to plant redwoods, and, after starting my own redwood grove, I keep planting seedlings in pots, and give them away to friends and neighbors.

My tree seedlings come in the mail from a tree nursery in the redwood country on the north California coast. They are about six inches tall and come bare-rooted, fresh from plastic tubes where they have sprouted from seed. I put them in fresh soil, mixed with perlite, as they grow best in their early years in a gritty light soil mix. They do best in full sun with occasional thorough watering in the summer. They thrive here, finding the north Oregon coast a good place for their new home. Our climate is warming and becoming drier, so what grows well here is changing.

A few years ago, I visited a nearby fish hatchery. The hatchery grounds had had a large redwood tree growing there, which was a local landmark. But, recent additions to the hatchery ponds had necessitated cutting down the old redwood. I had heard the hatchery staff missed their tree, and I went there to offer them a new tree.

We had a good talk, about salmon and trees and how we all have to adapt to change. The manager loved the idea of a new redwood tree, and also asked if I had more than one. I drove home and gathered up all my baby redwoods, and returned to the hatchery. The manager wanted four trees, and showed me the spots where they would go. He helped me unload them, and saw that I had more trees.

Like a scene out of a Charles Dickens novel, he asked for “more”. He managed another fish hatchery, and that place also was in need of some redwoods. He grinned broadly as we unloaded the rest of the seedlings, which had all grown at least two feet over the summer.

“They will find a good home,” he said. “And you can come visit them.”

A neighbor liked my redwoods, and has planted several, as living memorials to family members. A friend has several growing on his land, down by a creek. Another friend, fresh from an anniversary trip to the redwoods in California, now has several trees growing near her house, as a way to honor the trees, and keeping alive her memories of one of her favorite places in the world.

“Now, I get to see redwoods every day,” she says. “They make me happy.”

A friend and I celebrated his acceptance into nursing school and our trip to the California redwoods by planting a seedling in my grove.

Another friend, who owns a nursery, has heard my story about the trees. Last year, she took in my annual “crop” of trees and sold them at her nursery. And, last week, she asked me for more.

When I placed my order, the California nursery clerk asked me what I did with all the trees I ordered. I’m a regular customer now, and am on their Christmas card list. I told her my story and the stories of my tree loving friends and neighbors, and the fish hatchery manager.

She said I was a facilitator, a “Sequoia Facilitator” and we laughed. I’m going to add that to my resume, and order a T shirt with the slogan. There will have to be a drawing of a redwood on the T shirt, of course.

My redwoods are now thriving in over a dozen locations, some of which are unknown to me. I like that idea, that my trees are in places unknown to me, a mystery not to be solved. Like a lot of things in life, the seeds we plant, the impact we have on others, is often not known to us, yet that work, those gifts, like our acts of kindness, are probably the most important contributions we can make in this world. Tree planting and gifting is a great metaphor for our mission here in this life, what we should be doing — making a difference.

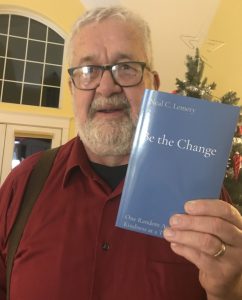

Books: NEW book – BE THE CHANGE – One Random Act of Kindness at a Time; Neal’s other books include: Building Community: Rural Voices for Hope and Change; Finding My Muse on Main Street, Homegrown Tomatoes, and Mentoring Boys to Men

.png)